Brains are freakin awesome, at first sight it may seem like a cesspool of chemicals (dopamine, serotonin, GABA, Glutamate, the list goes on), convoluted connections, and a chaos of electricity. But as you look deeper and deeper, and truly begin to observe these dynamics while the brain does what it does best – manage all your behavior – you begin to find shocking trends and patterns.

This is partly the mission of a neuroscientist – to observe and manipulate this chaos so as to discover some sort of order amidst the disorder. This moment of discovery feels surreal, almost ecstasy, its addictive. But in no way is it easy, it requires months to years of fine tuning, lots of hard work, and maybe a little luck.

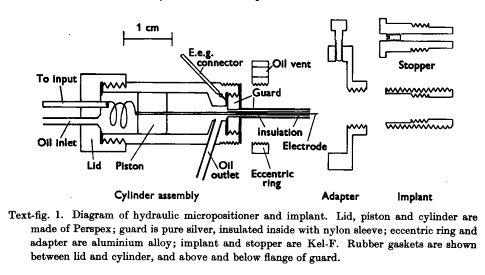

Hubel and Wiesel’s work is a classic example of this. (Hubel 1960) They presented a variety of visual stimuli to cats while recording electrical signals from the brain.They designed this swanky implant, for such a task:

It’s a technical challenge to record electrical activity from an area of the brain while an animal is moving. As we move around and interact with the environment, micro-vibrations enter our body and brain. Hubels team realized these micro-vibrations could offset the location of an electrode in the brain, which is why they designed this micropositioner. It allows for real-time adjustment of electrode height in the brain. Moreover, say an electrode failed, they could easily switch it out for a new one.

Their paper in 1959, had implants in thirty-five cats which is indicative of how low-throughput this technique. It’s also indicative of how amazing their discovery is – they quite literally found a needle in a haystack. The needle being neurons that encode receptive fields in our visual field and the haystack being the billions of neurons in a cat brain. Fortunately, neuroscientists have come a long way since then. Their techniques have drastically improved and there are more of them asking more questions (it’s a bit overwhelming at large conferences).

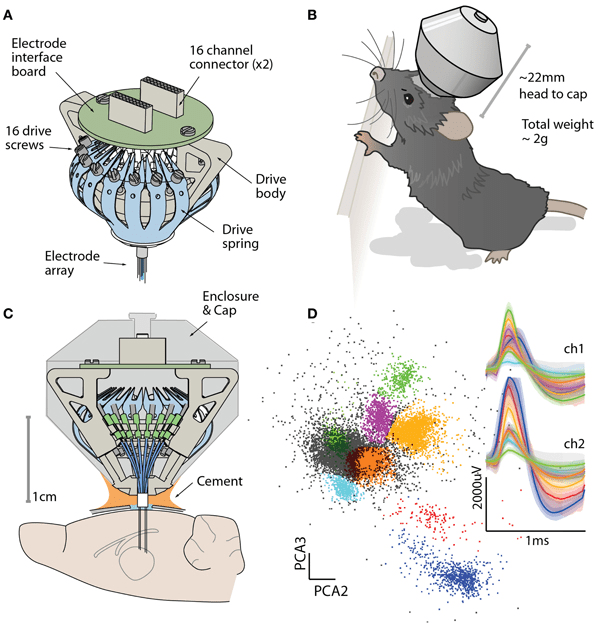

Instead of a hydraulic micropositioner, neuroscientists have use microdrives (although this is a small niche of the greater community). It’s a cone that sits on an animals head and allows an experimenter to independently adjust the height of up to 16 electrodes. HUGE upgrade from Hubel and Wiesel’s work. There are a few publicly available designs, but the most popular is the flexDrive (Voigts 2013):

This design was open-sourced by a few MIT scientists and is strides forward from what Hubel did.

I worked at Massachusetts General Hospital studying the brains of Alzheimer’s model mice using flexDrives. The drive is assembled by hand using a series of cannulae, 3D printed parts, electrode wire and more. Over the course of six months, I built dozens of drives under a microscope. It was a huge learning process as the parts are very fragile – a single kink in the electrode wire meant replacing it. Adhesive were the most stressful part of the build process because it can wick into nooks and crannies of the drive which would later impede movement of electrodes.

I loved building microdrives because it was so fulfilling – build process then implantation surgery and finally, recording of single neurons. In the electrophysiology room, I would watch single neuron spikes and say: ‘Yeeeeetttttt, those spikes exist because of me!’ But, as I had become expert level in building microdrives, I realized there is much room to innovate. This was just as I left MGH to go back to classes at my university.

In the next couple of years, I joined a few labs where I worked with other techniques like calcium-imaging, amperometry, voltammetry, and fMRI. I was fortunate to have been exposed to this large suite of tools in a few years. Appropriately so, I learned a few things: 1. No technique is easy to use, they all have their weaknesses both in the data and the methodology. 2. Each technique has a niche or a few niches of neuroscientists linked to it ie. neurochemists, pathologists, etc. 3. Every year, there are small updates and improvements to the tools.

It made me wonder something, is it at all possible to combine these tools? Amperometry and calcium-imaging in parallel could provide insight on how changes in glutamate levels align with firing rate. But, this is a technical challenge as an animal could never support the weight of both these biosensors. However, we could combine electrophysiology with these tools.

A conical microdrive occupies all real-estate on a mouse’s skull both in terms of space and weight. Appropriately so, no experimenter would ever consider implanting a microdrive alongside an amperometry probe OR calcium-imaging camera. This motivated me to design a modular microdrive, one that can operate on a quadrant system.

The MARS drive, short for multi-assay recording system, was my senior project and thesis at Northeastern University. There are four main configurations, the quarter drive, half-drive, three-quarter drive, and full-drive. I’ve included the github, video, and thesis if you’d like to learn more.

Github:

https://github.com/gbekheet/MARSDrive

Thesis:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=12ruAkfMih2_up4Y8E-wtcMAzqw61NAD6

References:

- Hubel, D. H. (1960). Single unit activity in lateral geniculate body and optic tract of unrestrained cats. The Journal of Physiology,150(1), 91-104. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1960.sp006375 (http://hubel.med.harvard.edu/papers/Hubel1960Jphysiol1.pdf)

- Voigts, J., Siegle, J. H., Pritchett, D. L., & Moore, C. I. (2013). The flexDrive: An ultra-light implant for optical control and highly parallel chronic recording of neuronal ensembles in freely moving mice. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience,7. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2013.00008 (https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnsys.2013.00008/full)